Literature review on DNA methylation mapping of historical DNA (hDNA), collected from museum specimens. Prepping for SIFP proposal to work with Andrea Quattrini at the Smithsonian NMNH.

What is hDNA?

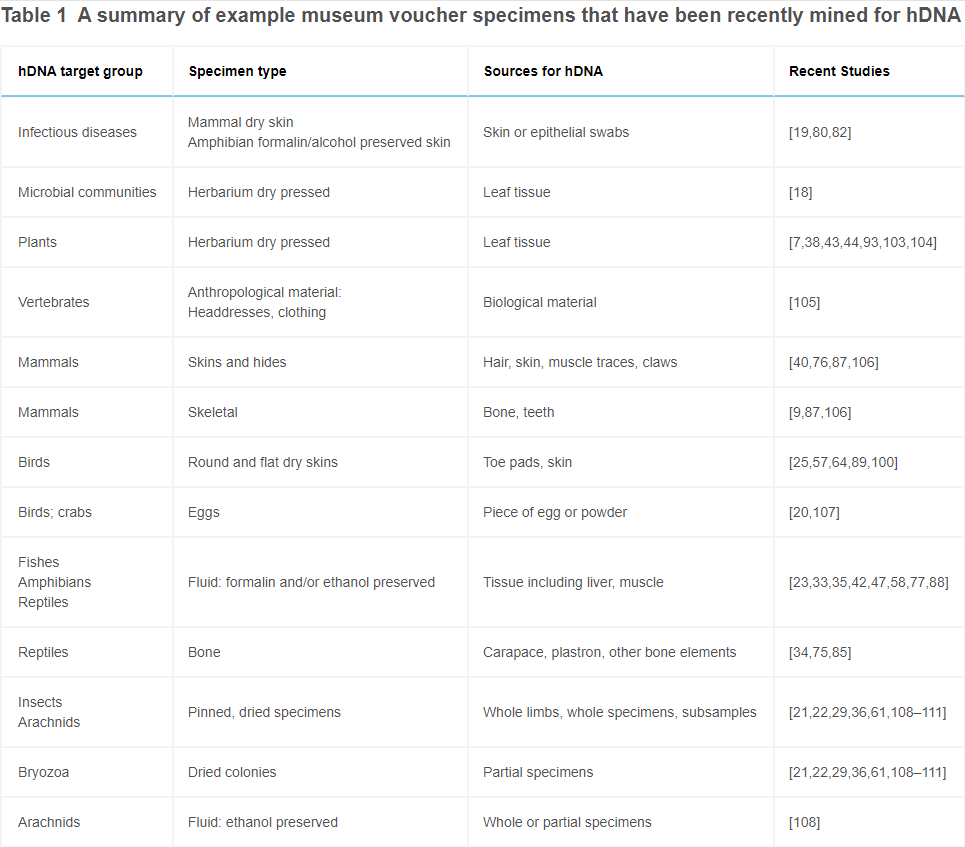

Raxworthy and Smith (2021) define historical DNA (hDNA) as “the DNA fortuitously contained in the tissues of traditional voucher specimens that are stored in museums and herbaria,” usually <200 years old. Importantly, this is distinguished from ancient DNA (aDNA), which is “DNA recovered from organic material (e.g., bone, plant matter, environmental samples, and subfossils) that is preserved under natural conditions” and is often much older, more degraded, and lower quantity than hDNA. It is also distinguished from tissues collected expressly as DNA samples (and their extracts), which Raxworthy and Smith term “modern DNA.”

For the purposes of this proposal, hDNA would potentially be collected from dried and liquid-stored coral specimens, preferably those collected ≥100 year ago. This age preference has two reasonings. First, beginning in the early 1900s many museum specimens were “fixed” (preserved as fluid voucher specimens) in formalin, a formaldehyde solution, which we now know presents many complications for DNA work. Second, for this project the value of museum archives lies in their collections of specimens that predate the serious impacts of anthropogenic climate change and environmental disturbance. Older specimens will yield epigenomes more useful for comparison to those of modern counterparts.

Challenges of working with hDNA

There are a lot of challenges to working with hDNA in general.

Contamination

Contamination with exogenous DNA (from an organism other than the specimen itself) can happen at any point during the collection, processing, transport, storage, or additional handling of the specimen.

DNA degradation

Both dry- and wet-stored specimens stored at room temperature gradually lose high molecular weight DNA and overall DNA quantity over time. In addition, specimens stored in alcohol can suffer hydrolytic damage if alcohol concentration drops due to evaporative loss (which is a universal problem for large collections). For fixed specimens, formalin can cause cross-linkages between DNA and other protein/DNA molecules and cause increased DNA damage like deamination and depurination. (Raxworthy and Smith (2021))

Cytosine deamination

Particularly relevant to this proposed project, DNA also undergoes cytosine deamination overtime. This is a spontaneous process in which cytosine residues are converted into uracil or hydroxyuracil. These are then observed as C-T and G-A transitions when deaminated cytosines are incorporated into a polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Notably, while “unmethylated cytosines are deaminated into uracils, causing CpG → UpG modifications; methylated cytosines, on the other hand, are deaminated into thymines at a faster pace, which results in CpG → TpG patterns.” (Niiranen et al. (2022))

This is super important in the consideration of hDNA for DNA methylation work, because the methods we use to map DNA methylation also use a CpG → UpG modification. The most common tool used to map DNA methylation is Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), which converts unmethylated cytosines into uracils, which are then sequenced as thymine (CpG → UpG → TpG). Remaining CpGs represent the methylated cytosines of the original sequence. That means deaminated cytosines, either methylated or unmethylated, would appear to be unmethylated following WGBS since all deaminated cytosines would ultimately be sequenced as TpG.

What is the timescale of cytosine deamination? Would specimens 100-200 years old have experienced sufficient cytosine deamination to significantly affect methylation mapping? How does the answer to this vary across preservation mediums (dry, alcohol, formalin)?

Previous methylation work using hDNA

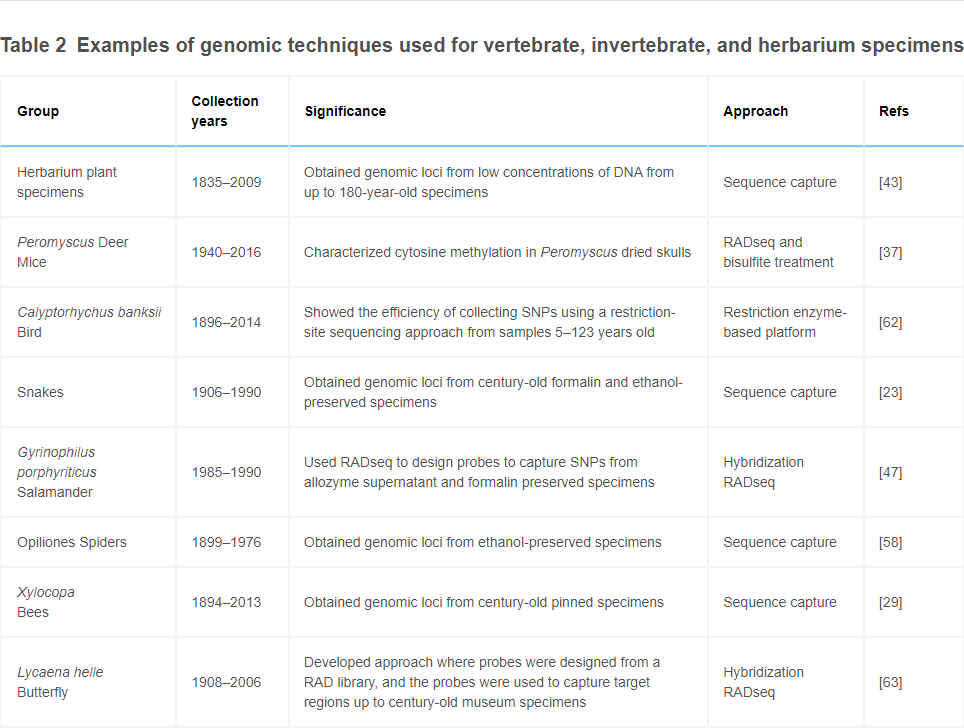

I’ve only found one paper so far that has trialed hDNA methylation mapping, and the authors also conclude they are the only example (at the time of publishing, in 2019).

Rubi, Knowles, and Dantzer (2020)

75 specimens of mice (40 white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus noveboracensis) and 35 woodland deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus gracilis))

traditional museum skull preparations (dried skulls stored at room temperature)

Collected in same locality in Menominee county, Michigan, over three collecting periods spanning 76 years (1940, 2003, and 2013–2016)

For the older specimens (13yo and 76yo), improved sequencing results decreased quickly past 5X read depth. In other words, while 5X depthwas a big improvement on 1X, 10X depth was not much different from 5X. This suggests that higher sequencing depth is important when working with old material, but has diminishing returns.

Interestingly, while the youngest specimens (0-3yo) yielded much higher global methylation rates than the older groups (13yo and 76yo), the two older groups did not have significantly different global methylation rates. So while new material is much more successful, past ~10 years all older material has similar global methylation rates?

Regional methylation patterns did not differ significantly due to specimen age

There was no notable signal of read end deamination. However, this may be the result of including a double digestion step, which cleaves DNA at both ends and may have “cut off” the more highly deaminated read ends. The slightly reduced global methylation rate of the 76yo group, in comparison to the 0-3 yo group, may indicate cytosine deamination in the oldest group.

Recommends steps to reduce sequencing of deaminated sites (e.g. a double-digestions step, as included in this study, or uracil-DNA-glycosylase and endonuclease VIII, which can be used to remove uracils prior to bisulfite treatment, preventing the sequencing of unmethylated cystosines that have been deaminated into uracil)

Recommendations for increasing yield from historic specimens:

Reduce size selection window to compensate for DNA fragmentation. Note that, while selecting smaller fragments would increase yield, it may also reduce the number of homologous loci sequenced across individuals, which may reduce ability to compare methylation patterns if sample size is low.

Steps to minimize DNA degradation during bisulfite treatment, e.g. shortening bisulfite incubation time. Note, however, that this could also reduce conversion efficiency.

Could remove the double digestion step, as this may have contributed to DNA fragmentation issues. Note, however, that this may lead to more issues with read-end deamination signal, as discussed above

Methods for DNA methylation mapping

ChatGPT Summary:

Here’s a comparison of different methylation mapping tools/methods based on cost, suitability for degraded/low-quantity DNA, use with partial cytosine deamination, and how established the method is:

Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

Cost: High. WGBS sequences the entire genome after bisulfite treatment, making it the most expensive option due to the amount of sequencing required.

Use with degraded/low-quantity DNA: Less suited for highly degraded DNA or very low quantities due to the need for large amounts of starting material and good quality DNA.

Use with partial cytosine deamination: WGBS relies on bisulfite treatment, which deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracil (later read as thymine). Partial deamination could lead to incomplete conversion, impacting accuracy.

How well established: Very well established. WGBS is considered the gold standard for methylome analysis, providing comprehensive genome-wide methylation data.

Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing (Targeted BS)

Cost: Moderate to high, depending on the number of regions targeted. It is more cost-effective than WGBS since only specific regions are sequenced.

Use with degraded/low-quantity DNA: Better suited for degraded or low-quantity DNA compared to WGBS because it focuses on specific regions, requiring less input material.

Use with partial cytosine deamination: Similar to WGBS, it relies on bisulfite conversion, so incomplete conversion can affect results. However, focusing on smaller regions may allow more control and validation of conversion efficiency.

How well established: Well established. Targeted BS is widely used for focused methylation studies, especially in candidate regions like promoters or CpG islands.

Enzymatic Methyl-seq (EM-Seq)

Cost: Moderate. EM-Seq offers a more cost-effective alternative to WGBS with a similar level of genomic coverage but without bisulfite treatment.

Use with degraded/low-quantity DNA: More suitable than WGBS for degraded or low-quantity DNA because it uses an enzyme-based approach that is gentler than harsh bisulfite treatment.

Use with partial cytosine deamination: EM-Seq avoids bisulfite-induced cytosine deamination by using enzymatic conversion, making it ideal when bisulfite’s harsh chemical treatment might cause issues, including incomplete conversion.

How well established: Relatively new. EM-Seq is a promising alternative to bisulfite-based methods but is not yet as widely adopted as WGBS or Targeted BS.

Target Enriched EM-Seq

Cost: Moderate, less than WGBS but more than basic bisulfite methods.

Use with degraded/low-quantity DNA: More suited for degraded DNA since the enzyme-based method is gentler.

Partial cytosine deamination: Avoids bisulfite-induced damage, reducing errors tied to incomplete deamination.

How established: New but growing in popularity as an alternative to bisulfite sequencing, especially for focused regions.

Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) Treatment

Cost: Variable, typically added on to bisulfite sequencing workflows (e.g., WGBS or Targeted BS).

Use with degraded/low-quantity DNA: UDG treatment is part of a preprocessing step to improve the accuracy of bisulfite sequencing but does not make it inherently better for degraded/low-quantity DNA.

Use with partial cytosine deamination: UDG treatment improves bisulfite sequencing by removing uracils generated from deaminated cytosines, which helps prevent errors from cytosine deamination that occur before bisulfite treatment. This leads to more accurate differentiation between methylated and unmethylated cytosines.

How well established: Well established, but UDG treatment is typically used in combination with other methods (e.g., WGBS) to improve accuracy rather than being a standalone method.

Methylation-Sensitive Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (MS-AFLP)

Cost: Low to moderate. MS-AFLP is a more affordable technique compared to sequencing-based approaches.

Use with degraded/low-quantity DNA: More suitable for degraded or low-quantity DNA, as it is based on PCR amplification and restriction digestion, which requires less starting material than sequencing-based approaches.

Use with partial cytosine deamination: MS-AFLP does not use bisulfite treatment, so partial deamination is not an issue. However, it depends on restriction enzymes sensitive to methylation status, so results can be impacted by incomplete digestion.

How well established: Long established but less widely used in high-resolution methylation studies compared to sequencing methods like WGBS. It’s an older method useful for specific applications, such as detecting overall methylation patterns or comparing methylation between samples.

Methylated CpG Binding Domain Sequencing (MBD-seq)

Cost: Moderate. MBD-seq involves selective enrichment of methylated DNA, followed by sequencing, making it less expensive than whole-genome methods like WGBS but potentially more expensive than targeted approaches depending on the depth of sequencing required.

Use with degraded/low-quantity DNA: More tolerant of low-quantity DNA than WGBS, but highly degraded DNA can be problematic, as larger fragments are better for efficient methylated DNA capture.

Use with partial cytosine deamination: Not impacted by cytosine deamination because MBD-seq relies on binding to methylated CpG sites via a protein domain, not on chemical conversion. This makes it more robust when bisulfite-induced errors might be an issue.

How well established: Well established, though less commonly used than bisulfite sequencing-based methods like WGBS. MBD-seq is often used for cost-effective, genome-wide methylation profiling without full bisulfite sequencing.

MethylRAD

Cost: Low to moderate. MethylRAD uses methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes to digest and sequence methylated DNA regions, making it more cost-effective than sequencing-based approaches that require bisulfite conversion or whole-genome coverage.

Use with degraded/low-quantity DNA: Suitable for low-quantity DNA because it relies on restriction digestion and PCR amplification, but highly degraded DNA may still cause issues if fragments are too short to be efficiently digested.

Use with partial cytosine deamination: Not affected by cytosine deamination since MethylRAD does not use bisulfite treatment. Instead, it depends on restriction enzyme sensitivity to methylation, so it avoids issues related to incomplete bisulfite conversion.

How well established: Relatively new but gaining traction. It’s not as widely adopted as WGBS but is becoming a popular, cost-effective alternative for methylation analysis, particularly for comparative methylation studies.

Comparison Table

| Method | Cost | Degraded/Low-Quantity DNA | Partial Cytosine Deamination | How Established |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | High | Less suitable | Sensitive to incomplete conversion | Gold standard, very well established |

| Targeted BS | Moderate | Better suited | Sensitive to incomplete conversion | Well established |

| EM-Seq | Moderate | Suitable | Avoids bisulfite-induced damage | Newer, gaining popularity |

| Target Enriched EM-Seq | Moderate | Suitable | Avoids bisulfite-induced damage | Newer, promising |

| UDG Treatment (w/BS) | Variable | Neutral impact | Improves bisulfite accuracy | Well established with WGBS |

| MS-AFLP | Low/Moderate | Suitable | Not impacted by deamination | Older, less common |

| MBD-seq | Moderate | Suitable for low-quantity, less for degraded | Not impacted | Well established but less common |

| MethylRAD | Low/Moderate | Suitable, but not ideal for highly degraded DNA | Not impacted | Newer, cost-effective, growing |

Summary

Cost: WGBS remains the most expensive method, while MethylRAD and MS-AFLP are among the least expensive. MBD-seq is a mid-range option that provides genome-wide methylation information without full sequencing.

Degraded/low-quantity DNA: MethylRAD and MBD-seq handle low-quantity DNA better than WGBS, but highly degraded samples may still present challenges for both.

Partial cytosine deamination: MBD-seq and MethylRAD are unaffected by partial cytosine deamination because they don’t rely on bisulfite conversion.

How established: WGBS is the gold standard, while MBD-seq is a well-established alternative for methylation profiling. MethylRAD is newer but growing in popularity due to its cost-effectiveness and potential for comparative studies.

Nanopore Sequencing

An option that Steven mentioned as potentially useful is Nanopore sequencing. In this method, DNA (or RNA) molecules are fed through a nanopore, a tiny hole embedded in a membrane that separates two chambers of electrolyte solution. When a voltage is applied, an enzyme pushes the DNA molecule through the nanopore and fluctuations in the electric current are tracked. Specialized software can then be used to assign nucleotide at each position based on the current fluctuations.

While Nanopore sequencing was originally developed for standard DNA sequencing, softwares have been developed that can interpret Nanopore read data to identify methylated nucleotides (e.g., Ahsan et al. (2024)). This has many advantages over WGBS that could be really useful for working with hDNA.

As a reminder, the biggest hurdles when working with hDNA are likely to be 1) low DNA quantity, and 2) low DNA quality, including spontaneous cytosine deamination that converts CpG sites to either UpGs (unmethylated) or TpGs (methylated). Nanopore sequencing reads and detects nucleotides from a single DNA molecule at a time, meaning it works with much lower quantities of DNA than traditional sequencing methods. This also means that DNA amplification (i.e., PCR) is not required, so there are no biases introduced prior to sequencing. In addition, since Nanopore sequencing requires no modification of the DNA (e.g., bisulfite conversion), there is no introduced deamination, meaning deaminated cytosines will not be confused with intact methylated and unmethylated cytosines. Finally, as the cherry on top, Oxford Nanopore Technologies announced just a few months ago that they now have “the ability to detect damaged DNA bases, including genomic Uracil (dU) at 96.34% accuracy.” This means that, not only will Nanopore sequencing distinguish between intact and deaminated cytosines, it should be able to differentiate between deaminated cytosines (deaminated CpG → UpG) and deaminated methylated cytosines (CpG → TpG)!

I couldn’t find a description of the analysis changes that allow ONT to detect damaged DNA, but if that update is not yet publicly available, I also found a paper describing how to detect Uracil in DNA Békési et al. (2021), which would similarly allow you to discriminate cytosine deamination of methylated and unmethylated cytosine.

Notes for SIFP project:

If I’m trying to do a validation-type paper, which might hold the most water given how little hDNA methylation work has been done, would be best to use specimens of same species, collected from same location over multiple time points (ideally same reef).

Seems like big concerns are dealing with fragmented DNA and cytosine deamination. EM-Seq seems like the best option for addressing both of those, and it may be abit cheaper than WGBS! Only downside is that it’s not as well established, so I’m not sure how that might affect data analysis (are there existing tools?) or reporting/interpreting results.